|

The Return of the Prodigal Son - Week 4 - Journeying Home

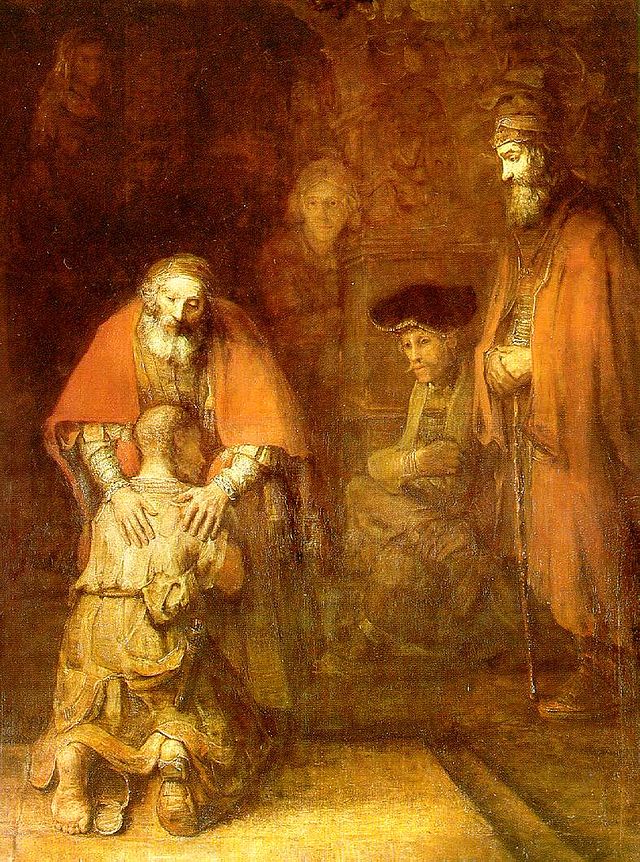

Last week we considered what it meant for the son to leave home. Today, we consider what it might mean for the son to return. AS Henri Nouwen reflects on Rembrandt’s painting on the Return of the Prodigal Son he writes: The young man held and blessed by the father is a poor, a very poor man. He left home with much pride and money, determined to live his own life far away from his father and his community. He returns with nothing, his money, his health, his honour, his self-respect, his reputation… everything has been squandered. As Henri Nouwen writes: Rembrandt leaves little doubt about the son’s condition. His head is shaven, suggesting the head of a prisoner whose name has been replaced by a number. His individuality has been stripped away like a prisoner in a concentration camp. Wanting to be completely free of the constraints of living with his father, ironically he has become a prisoner to his own desires which have led him to his ruin. The clothes that Rembrandt gives him in the painting are underclothes, barely covering his emaciated body. Both the father and the elder son in the painting are depicted wearing expensive red cloaks giving the status and dignity. The kneeling son by contrast is in rags which seem to just cover his emaciated, exhausted and worn-out body from which all strength has gone. The soles of his feet tell the story of a long, arduous and humiliating journey home. The bare left foot is scarred. The right foot is covered only partially by a broken sandal. Henri Nouwen writes that this is a depiction of a man who has found himself dispossessed of everything, except for one thing, his sword. The short sword depicted in Rembrandt’s painting, hanging from the younger son’s hips is the last remaining sign of his dignity and nobility. Henri Nouwen writes that what it shows is that even in the midst of his debasement, he has clung to the truth that he is still the son of his father. Otherwise, he would have sold his so valuable sword, the symbol of his sonship. Although he has come back as a beggar and an outcast and looking like a slave, he has not forgotten that he is still the son of the father. And in the end, it is this remembered and valued sonship that finally persuades him to turn back and go home. Going back to the pig sty, Henri Nouwen points to verse 16 which says that “He longed to fill his stomach with the pods that the pigs were eating, but no-one gave him anything.” Henri Nouwen writes that the younger son becomes fully aware of how lost he is when no one in his surroundings shows the slightest interest in him. When his money ran out he stopped existing for them. It is hard indeed to imagine what it means to be a complete stranger and foreigner, to be a person to whom no-one shows any sign of recognition. When no-one wants to give him the food that he is giving to the pigs, the younger son realises that he isn’t even considered a fellow human being. Even the pigs are treated with more value and care than the son. Henri Nouwen writes: I am only partially aware of how much I rely on some degree of acceptance and belonging in life. Common background, history, vision, religion and education; common relationships, lifestyles, and customs; common age and profession; all of these serve as a basis for acceptance. And so for all of us, whenever we meet a new person, we always begin by looking for what we have in common, a search for a common link that will help us to bridge the gap between ourselves and the person we have just met. The less we have in common, the harder it is to be together and the more estranged we feel in each other’s company. When there is no common language or common customs or when we do not understand a persons lifestyle or religion or rituals or art or even their food and their manner of eating, then the more we feel foreign and lost. And so Henri Nouwen writes that when the younger son is no longer considered human by the people around him, the more profoundly he experiences his isolation and loneliness. He is truly lost, and it is this sense of complete lost-ness that brings him to his senses. He is shocked into the awareness of his utter alienation. He is utterly disconnected from everything that gives life – family, friends, community acquaintances and even food. In Verse 16, living in a foreign country, he has become a non-person. All at once he sees clearly the path he has chosen and where it has led. And it is this that helped to bring him to his senses. Straight after verse 16 as he reaches the lowest point in his life, in verse 17 we read that “ he came to his senses”. And this is often the case. Sometimes the wheels have to fall off before we are able to see things clearly. Sometimes we have to hit rock-bottom to truly recognise the truth about ourselves so that we are ready to make the necessary changes. For the prodigal son, this coming to his senses involved a remembering and a rediscovery of his deepest self. Whatever he had lost, be it his money, his friends, his reputation, his self-respect, his inner joy and peace, he still remained his father’s child. And so he says to himself in verse 17 “How many of my fathers hired men have food to eat, and here I am dying of hunger”. As Henri Nouwen writes: The younger son’s return is expressed succinctly in the words of verse 18 “Father… I no longer deserve to be called your son.” On the one hand the younger son realises that he has lost the dignity of his sonship, but at the same time he is also aware that he is indeed the son who had dignity to lose. And so the younger son’s return begins at the very moment that he remembers and reclaims his sonship, even though he no longer feels worthy of it. It is the loss of everything that brings him to the bottom line of his true identity. In hitting rock-bottom, he hits the bedrock of his sonship his true identity. When he finds himself desiring to be treated as one of the pigs, he realises that he is not a pig, but the son of his father. And this realisation became the basis of his choice to choose life rather than death. In this moment he recognises and remembers his father’s love… a love that would treat even his hired workers with dignity and fairness. And it is this remembering of his father’s love, however misty this may have been, that gives him the confidence and the strength to claim back something of his sonship. And perhaps that is what this parable is trying to tell us, that no matter how lost and alienated from life and ourselves we may become our truest and deepest identity is that we are children of God. We have come from God and our truest identity is in God, and there is nothing that we can do that change this. Even if we may cease behaving like God’s children, it can never change the underlying fact that we are indeed God’s children. We are God’s offspring, everyone of us, even when we do not act like God’s children. And this applies even to the Putin’s of this world. And so he remembers his father’s love and in doing so, begins claiming ever so hesitantly his true identity. But he is not yet aware of the height, depth and the full extent of that love. And so as he journey’s home, considering his unworthiness, considering the full extent of his own crimes against his father, he rehearses an imaginary conversation in his head with his father. I wonder how many imaginary conversations each one of us have had. I think it is quite common. Henri Nouwen writes: I am seldom without some imaginary encounter in my head in which I explain myself, boast or apologise, proclaim of defend, evoke praise or pity. It seems that I am perpetually involved in long dialogues with absent partners, anticipating their questions and preparing my responses. I am amazed by the emotional energy that goes into these ruminations and murmuring. He writes: Yes, like the prodigal son, I am leaving the foreign country. Yes, I am going home… but why all this preparation of speeches which will never be delivered? The reason is clear, he writes. Although claiming my true identity as a child of God, I still live as though the God to whom I am returning demands an explanation. I still think of his love as conditional… I keep entertaining doubts about whether I will be truly welcome… I am not yet able to fully believe that where my failings are great, God’s grace is even greater. In the end God does not receive us back because of our clever arguments or rehearsed confessions. In the end, all that is required of the prodigal son when he finally meets his father is simply to surrender into his father’s loving embrace. And it is this that Rembrandt captures so beautifully in his painting. The son collapses on his knees before the father, surrendering into his embrace as he rests his head into his father’s chest, like a little child in his fathers arms. In this moment, he has become like a little child again. In fact it was a young women who pointed out to Henri Nouwen that the head of the younger son looks like the head of a baby who has just come out of his mother’s womb. Pointing to the painting she said, “Look, it is still wet and fetus like.” In the light of his father’s loving embrace, the shaved head of the prisoner or slave has become the face of a newborn baby resting it’s head on it’s mothers breast having just been delivered from her womb. The pain of lostness has become the pain of new birth in the arms of his father’s love. Is this perhaps an image of what Jesus meant when he said that if we are to enter into the Kingdom of God, which might be paraphrased as entering the Embrace of God’s Eternal love, we need to become like little children. In Rembrandt’s painting, as the son collapses wearily into his father’s embrace and surrenders his head into the folds of his fathers clothes, it is as though he has been born anew and gifted with a new innocence. And what it took was not some clever argument or negotiation about working as one of his father’s hired hands. What it took was a final surrendering of everything he had left into the unconditional embrace of the father’s love. In some ways it is an image of what all of us will end up doing as we breath our last. In that last breath what else will we be capable of, except to surrender and to let go and rest our weary heads into the unconditional embrace of God’s love. It is from God’s love that we have come, and in the end it is into God’s unconditional love that we will all have to surrender. I close with a quote from scripture: 1 John 3:2 “Dear Friends, we are already God’s children, but what we will be has not yet been made known.”

0 Comments

The Return of the Prodigal Week 3 - Leaving

I’d like to begin today by reading a very short anonymous poem about leave home: It is written on a post card from two parents to their daughter. In the address section is written: the Great Unknown, Far, Far Away and the poem reads as follows: Dearest daughter, Be careful. We trust you. We love you. Mom and Dad In those simple words is captured a whole range of thoughts and sentiments. A deep sense of love and care that has been nurtured and treasured over the daughter's lifetime, from her conception through childhood and teens and into adulthood… Dearest daughter, we love you. A sense of anxiety and worry over what could potentially go wrong. Be careful. The sense that she has grown and matured and has developed the skills to make it on her own. We trust you. And reading between the lines, the underlying sense of sadness that inevitably comes with having to let go expressed in the address: The great unknown, far far away… Dearest daughter, Be careful. We trust you. We love you. Mom and Dad Today we continue our preaching series on the Return of the Prodigal Son, a reflection on the parable that Jesus tells in Luke 15 but also a reflection on a book written by Henri Nouwen reflecting on Rembrandt’s painting by the same name. As Henri Nouwen reflects on the full title of Rembrandt’s painting ‘The Return of the Prodigal Son’, he writes that implicit in the return is a leaving. Returning is a home-coming only after a home-leaving, a coming back after having gone away. He writes: “The father who welcomes his son home is so glad because ‘...this son was dead and has come back to life; he was lost and is found’. The immense joy in welcoming back the lost son hides the immense sorrow that has gone before. He writes that only when we have the courage to explore in depth what it means to leave home, can we come to a true understanding of the return. In Rembrandt’s painting of the Prodigal Son, the sorrow and pain of leaving is depicted most profoundly in the rags of the son as he returns. But the depth of pain and sorrow are not just the son’s who has discovered the harshness of life outside of his father’s embrace. The sorrow is indeed also the sorrow and the anguish of the father who has watched his beloved younger son leaving home not as a means of growing to full maturity, but rather with a desire to avoid taking responsibility. With sorrow in his heart, the father has had to watch the son leave, knowing that disaster is surely awaiting the son, but it is the only way he will ultimately grow. Knowing also that if he tried prevent his son from leaving, he would lose his son’s love anyway. If you love someone, you will in the end need to set them free. Like Jesus who doesn’t run after the Rich Young Man, the father in the parable does not run after the son, for the son needs to make the necessary mistakes that will hopefully in the end lead him back home. Henri Nouwen tells how Kenneth Bailey offers a penetrating explanation of the gravity of the son’s leaving. He quotes Kenneth Baily who writes: For over fifteen years I have been asking people of all walks of life from Morrocco to India and from Turkey to the Sudan about the implications of a son’s request for his inheritance while his father is still living. The answer has always been emphatically the same… the conversation runs as follows: Has anyone ever made such a request in your village? Never! Could anyone ever make such a request? Impossible! If anyone ever did, what would happen? His father would beat him of course! Why? The request means – he wants his father to die. The implication of the son’s request is ‘Father, I cannot wait for you to die’. As Timothy Keller writes, the request shows that the younger son loves his father’s money more than he loves his father. It is the father’s stuff that he wants, not his father’s love. The son’s leaving is therefore more than just an offence to the father, it is a heartless rejection of the home in which the son was born and nurtured and a break from the whole tradition upheld by the larger community of which he was a part. One could say it is an act of profound self-centeredness and a betrayal of the treasured values of family and community that have nurtured and formed him, as he chooses to dispose of his father’s assets and leave for a distant country rather than to give back out of gratitude for all he has received in life. But this parable is not just about leaving home in a literal sense. It is meant to be read as a parable, a metaphor for those times when we feel disconnected from the inner life of our own spirits. And so Henri Nouwen writes that leaving home is much more than an historical event bound in time and space. Rather, it is a denial of the spiritual reality that I belong to God, that God holds me safe in an eternal embrace, that I am indeed carved in the palms of God’s hands and hidden in their shadows. Leaving home means ignoring the truth that God has fashioned me in secret, moulded me in the depths of the earth and knitted me together in my mother’s womb. Leaving Home is living as though I do not yet have a home and so must look far and wide to find one, when all along I already have a home in God’s gentle embrace. Henri Nouwen goes on. He says “Home is the centre of my being where I can hear that voice that says: “You are my Beloved, on you my favour rests”. To leave home for a distant country as the prodigal son does, is to cease to hear that voice of God that whispers our name and calls us the Beloved. And in it’s place to seek other ways to fill the void that is left. Leaving home means seeking, in other things, and in other people, a depth of satisfaction, contentment and love, that only God can bring. To leave home in a spiritual sense, is to cease finding our fulfilment in things that are of eternal and enduring value and to put our hope and our trust in things that are impermanent, passing and of fleeting value. By contrast, if we find ourselves deeply rooted in the world of the spirit, and grounded in a sense of the eternal, then it is possible to appreciate and enjoy the fleeting joys of life, because we are rooted in something deeper. Is that perhaps what it means to be in this world but not of this world? But when we fail to root ourselves in our true inner home of the spirit, then chasing after the fleeting joys of life becomes like chasing after the wind as we read in Ecclesiastes. It is a recipe for desperate, futile, empty and addictive living as the younger son very quickly discovers as he finds himself hitting rock-bottom feeding pigs and longing to eat their food. We can only appreciate the joys of our outward senses in the material world when we are rooted in the more enduring and deeper joy of the spirit, our true home. As I suggested earlier, the fatal mistake of the younger son in this parable is that he wanted to enjoy only the good things of life. Leaving home was an exercise in avoidance. He was trying to avoid growing up, trying to avoid the pain and the difficulties of life as an adult and so soon he finds himself far away from his father’s love, living alone, in a pig-sty in a distant country. And there he discovers for himself that pain and struggle in life cannot in the end be avoided. When we live our lives trying to avoid the pain, the struggles and the responsibilities of life, we end up in even greater pain and suffering than we were avoiding in the first place. We all find ourselves from time to time living in distant countries away from ‘the love of the father’. To live in a distant country is a metaphor for the dead-ends where we have searched for love, affirmation, value and satisfaction, but found only emptiness, broken promises and constantly shifting sands. Henri Nouwen writes: “I am the prodigal son, every time I search for unconditional love where it cannot be found. Why do I keep ignoring the place of true love and persist in looking for it elsewhere? Why do I keep leaving home where I am called a child of God, the Beloved of my Father?” Henri Nouwen writes that it is not very hard to know when we are being dragged into a distant country away from our true spiritual home. Fear, anger, resentment, greed, anxiety, jealousy, a sense of barreness and emptiness are all signs that we have left home, perhaps daydreaming about becoming rich, powerful and famous, and in the process disconnected from the inner voice of love that is already whispering: “You are my beloved, on whom my favour rests?” What are the times in your life where it has felt psychologically or spiritually you were living in a distant country? What are some of the dead-ends you have found yourself over the years? What are the places and occasions in your life where you were hoping to find satisfaction and contentment, (perhaps even unconditional love) but only found emptiness, like you had been chasing after the wind? The Return of the Prodigal Son - Week 2 - Rembrandt the Prodigal & Rembrandt the Father

Last week I did an introductory sermon to a new sermon series on the Parable of the Prodigal Son. As an aid to exploring this parable in greater depth I will be using a book written by Henri Nouwen called “The Return of the Prodigal Son”. The book in turn is a reflection on Rembrandt van Rijn’s painting by the same name, a painting that Rembrandt painted very near the end of his own turbulent and tumultuous life. As I shared last week, the painting by Rembrandt is a beautiful and moving depiction of the moment the prodigal son meets and is embraced by his father when he returns home. The kneeling son rests his face onto the father’s chest as the elderly and partially blind father places his hands gently over the son’s shoulders as he receives the lost and now destitute son with warmth and tender love, back to himself. There is a beautiful stillness to the painting, almost as though Rembrandt has captured a moment of eternity on canvas. Henri Nouwen suggests that this painting reveals how by the end of his life, an inner transformation had taken place, with a deep sense of having developed an inner vision and a spiritual insight that he did not have in his younger years. Henri Nouwen writes that in Rembrandt’s younger years, Rembrandt had all the characteristics of the prodigal son. He was… “brash, self-confident, spendthrift, sensual, and very arrogant.” Henri Nouwen writes that at the age of 30 Rembrandt painted himself as the lost son in a brothel, with his wife Saskia painted as one of the ladies of the brothel. Rembrandt painted himself with his half-open mouth and lustful eyes holding up a half-empty glass while with his left hand he touches the lower back of the girl who appears to be seated on his lap. It is a portrait of merriment and sensuousness, that perhaps captures something of the character of Rembrandt in his younger years. Henri Nouwen writes that all of Rembrandt’s biographers describe him as a proud young man, strongly convinced of his own genius and eager to explore everything that the world has to offer; an extrovert who loved luxury and was quite insensitive towards those around him. In addition, like the younger son in the parable, one of Rembrandt’s main concerns was money. Rembrandt made a lot, spent a lot and also lost a lot. Nouwen writes that a large part of Rembrandt’s energy was wasted in long drawn-out court-cases about financial settlements and bankruptcy proceedings. Nouwen writes that other self-portraits of this period reveal Rembrandt as a man hungry for fame and adulation, fond of extravagant costumes, preferring golden chains to the traditional starched white collars, and sporting outlandish hats, berets, helmets and turbans. After Rembrandt’s short period of success, popularity and wealth as an artist what followed was a period of much grief, misfortune and disaster. He lost 3 children over a five year period from 1635 – 1640. Two years later his beloved wife Saskia died in 1642. After her death he had an affair with a women he had hired to look after his nine-month-old son Titus, which ended in disaster. After that disastrous period of his life he had a more stable union with another women, Hendrickje Stoffels who bore him a son who died in 1652 and a daughter, Cornelia. Henri Nouwen writes that during these years, Rembrandt’s popularity as a painter plummeted and in 1656 Rembrandt was declared insolvent, having to sign over all his property and effects for the benefit of his creditors in order to avoid complete bankruptcy. In doing so he lost all of his possessions, all of his own paintings as well as his collection of other painters works, his large collection of artefacts, and his house in Amsterdam with all it’s furniture. When Rembrandt died in 1669, he had become a poor and a lonely man. Only his daughter Cornelia, his daughter-in-law Magdalene van Loo and his granddaughter Titia survived him. His common law wife, Hendrickje had already died 6 years earlier and his son Titus had died a year before his own death. And yet, rather than becoming bitter and twisted by this tumultuous life; rather than wallowing in his own pain and self-pity, this life of excess, leading to disaster and loss had a purifying effect on him. In a way his life of ruin and loss led him in a movement away from the glory of the world that seduces with all it’s glittering lights to a discovery of the inner light of old age, the glory that is hidden in the human soul which surpasses death. While his own story had begun in excess and waste like the prodigal, in a very profound way, it was that very journey that led him to the Inner Light of God’s grace and compassion that is expressed so profoundly in his painting of the Return of the Prodigal Son. In a way, by the end of his turbulent life, Rembrandt had indeed become the prodigal who was now ready to return Home to God. In a very real sense, the prodigal son depicted kneeling before his father is a depiction of Rembrandt himself. It was he who had learned by the end of his life how to kneel before the God who had made him and loved him, it was he whose pride and brashness had been transformed into humility and surrender before the tender Love of the Divine. But in another sense, Henri Nouwen suggests that Rembrandt was not only the younger son in this painting returning home to the father. In a very real sense, by the end of his life, Rembrandt had indeed grown to become also the gentle, welcoming, tender father depicted in the painting. The only reason that Rembrandt could the gentle compassionate embrace of the father was because that gentle wisdom and compassion of the father had begun to dwell within himself as well. Nouwen writes: “One must have died many deaths and cried many tears to have painted a portrait of God in such humility”. At the end of his life he was indeed the prodigal who had begun to find his way home to God, but in another sense the gentle, loving and welcoming father had come to dwell within the sanctuary of his own heart. The journey of the Protestant, Reformed painter, Rembrandt Van Rijn from being the prodigal son in his youth to somehow also becoming the father in the parable by the end of his life, is, in a different way, paralleled in the life of the Dutch Catholic Priest Henri Nouwen whose life had become so deeply affected by Rembrandt’s painting. As I shared in last weeks sermon, when Henri Nouwen had first encountered the painting, it was the prodigal son that had so captivated his attention. He had realised that he was that son. He was looking for a place he could call home. He was the one who felt lost and longed to be embraced. But a few years later, while discussing the painting with a trusted friend in England, his friend had looked quite intently at Henri and said, “I wonder if you are not more like the older son?” With those words, his friend had opened up a new space within him. He had never thought of himself as the older son, but the more he thought about it, the more he realised that there was indeed an older son living within him. He had always lived quite a dutiful life, just like the older son, When he was 6 years old, he already wanted to become a priest. He was born, baptised, confirmed and ordained in the same church. He had always been obedient to his parents his teachers, his bishops and indeed to God. He had never truly run away from home and had never wasted his time and money on sensual pursuits, and never gotten lost in debauchery and drunkenness. For his entire life he had been quite responsible, traditional, home-bound. And yet for all that he may well have been just as lost as the younger son in the story as he saw himself in a while new way. He writes: I saw my jealousy, my anger, my touchiness, doggedness and sullenness, and, most of all, my subtle self-righteousness. I saw how much of a complainer I was and how much of my thinking and feeling was ridden with resentment. I was the elder son for sure, he writes, but just as lost as his younger brother. I had been working very hard on my father’s farm, but had never fully tasted the joy of being at home. Having first identified himself with the younger son in the painting, and then discovered that he was the elder son for sure, a few years later, he became challenged by another trusted friend, who again, when reflecting on the painting with him said to him, “Whether you are the younger son or the elder son, you have to realise that you are called to become the father… You have been looking for friends all you life; you have been craving for affection as long as I’ve known you; you have been interested in a thousand things; you have been begging for attention, appreciation, and affirmation left and right. The time has come to claim your true vocation – to be a father who can welcome his children home without asking them any questions and without wanting anything from them in return”. In writing his book on the Return of the Prodigal Son as few years after this conversation, Henri Nouwen writes: I still feel the desire to remain the son and never grow old. But I have also come to know in a small way what it means to be a father who asks no questions, wanting only to welcome his children home. Over the next few weeks, may we also discover within ourselves not only the lost children of God, but also the compassionate mother and father that is God. Amen. SERMON TEXT - Coming Home - The Return of the Prodigal - Introduction

I was the last of the three sons to leave home. My younger brother Wesley Who is about 4 years younger than me left home just after school at the age of 18 when he got a tennis scholarship in the US. The first time he came home a number of months later it was really wonderful. My Mom prepared everything in advance. She cooked his favourite food. On his pillow she placed his favourite crisps (Ghost Pops). When he arrived home, he knew that he had come home. I left home only about two years later at the age of 23 when I was accepted as a minister in training in the Methodist Church. I was moved around quite a bit in those early years living in four different places over a four year period. In some way it was an exciting time, but it was also an unsettling time and so trips back home to my Mom and Dad were just wonderful. It was wonderful to be able to return to the warmth and security of a place called home. But I am very conscious that there are many who don’t grow up in warm inviting and secure homes. For many home was and perhaps is been a place of insecurity, anxiety, trauma and abuse. There are many who at home don’t feel at home. But even for those of us who have grown up in fairly stable homes there are many who from time to time experience a strange feeling homesickness even when finding themselves at home. I read on the internet that in the Welsh language there is a word that expresses this mysterious feeling of being homesick even when you’re at home. It is the word: hiraeth. I understand that it is a word that can have a variety of shades of meaning. Samantha Kielar writes that hiraeth can describe “...a combination of a sense of homesickness, longing, nostalgia, and yearning, for a home that you cannot return to, or perhaps no longer exists, or even maybe never was. It can also include grief or sadness for who or what you have lost, losses which make your “home” not the same as the one you remember.” Lastly she says, one attempt to describe hiraeth in English says that it is “a longing to be where your spirit lives.” …” a sense of dislocation from the presence of spirit…. “a longing to be where your spirit lives”. I get the sense that this was the feeling that Henri Nouwen was experiencing when he first caught sight of a painting by the Dutch artist Rembrandt. Henri Nouwen was a Catholic priest who had been born in the Netherlands in 1932 and ordained in Utrecht in at the age of 25 at St Catherine's Cathedral in the city of Utrecht. He studied not only theology but also psychology and throughout his life he sought to integrate spiritual ministry with modern psychology. For a large part of his career he worked not as a parish priest but as an academic in a number of Universities in Europe and in the United States, most notably at Yale Divinity School and also as Professor of Divinity at Harvard Divinity School where he taught until 1985 when his academic career came to an end. By his late 40’s a restlessness began to grow in him. His work as a professor, a priest and a writer of spiritual books while also doing part time voluntary work a seminary in Central America kept his life going at a pace that was not really sustainable. And so he began to explore a new direction for his life and ministry, which led him to sit in the office of a women from the L’Arche community for the mentally handicapped in France. He was exploring with her the possibility of taking a sabbatical to live and minister for a year in one of the L’Arche communities for the mentally handicapped. He had just finished an exhausting 6 week lecturing tour around the United States. While sitting in that office talking about his plans for a sabbatical and a possible new direction for his life, Henri Nouwen became mesmerised by a poster of one of Rembrandt’s paintings that was hanging on the back of the door. It was Rembrandt’s painting of the Return of the Prodigal Son, a painting that he had finished in 1669 very near the end of his own turbulent life. It is a beautiful and a moving painting of the prodigal son’s homecoming when he meets his father. The prodigal son is depicted in a wretched, bedraggled and destitute state with clothes like rags hanging off his body, with only one shoe left, after having wasted his inheritance. The painting depicts the prodigal son kneeling before his father in repentance, seeking forgiveness, while the father, who is depicted as quite elderly and seemingly almost blind, receives him back with a tender and warm embrace; his hands placed gently and tenderly one over the prodigal’s shoulder and back as he draws his once wayward and lost son towards himself with love. In the painting there is a warm and gentle glow of light shining on the prodigal as he buries his face into the bosom of his welcoming father. Standing to the right is the older brother who seems set a little higher in the painting as though on a platform. His posture is bolt upright, his hands in a crossed, closed position as he appears to look down in a mixture of judgement, disgust, pity and disapproval. In addition to these three main characters in the painting are three others looking on from different positions in the painting each with expressions ambiguous enough to make one wonder what they are thinking of all of this. But for Henri Nouwen, the moment he laid eyes on the painting, it was the figure of the prodigal being received home with warmth and tenderness by the father that captivated his attention interrupting the conversation he was engaged in. As he looked on the painting with longing in his heart he writes of his own condition: I was dead tired, so much so that I could hardly walk. I was anxious, lonely, restless, and very needy. During the [recent 6 week trip] I had felt like a strong fighter for justice and peace, able to face the dark world without fear. But after it was all over I felt like a vulnerable little child who wanted to crawl onto its mothers lap and cry. It was in this condition that he found himself staring at Rembrandt’s painting of the return of the Prodigal Son. His heart leapt as he saw it. After his long self-exposing journey, the tender embrace of father and son expressed everything he desired at that moment. He was indeed exhausted from the long travels; He wanted to be embraced; He was looking for a home where he could feel safe. He writes that in that moment, “...the ‘son-come home’ was all I was, and all that I wanted to be. For so long I had been going from place to place: confronting, beseeching, admonishing and consoling. Now I desired only to rest safely in a place where I could feel a sense of belonging, a place I could feel at home.” In John 14:23 we read these words: “Anyone who loves me will obey my teaching. My Father will love them, and we will come to them and make our home with them.” Henri Nouwen writes that these words had always deeply impressed him with the profound insight ‘I am God’s Home’. It is not only that God, like the father in the parable is waiting with tenderness and love to welcome us home, but paradoxically and inexplicably, is it possible that God is also like a weary wanderer who is wanting to find a home, a resting place within us? I have quoted St Augustine before when he writes: O God, you have made us for yourself, and our hearts are restless until we find our rest in you. Is it possible that God’s heart is also restless until God finds God’s rest, or God’s home, in us. What could it mean to come home to God? Not later we die in the sky by and by, but here and now, in this world of crisis and conflict, today? And what could it mean to make our hearts a place where God can find a home? Over the next few weeks I would like to invite you to join me as we explore the Parable of the Prodigal Son in greater detail, and with insights from Henri Nouwen, Rembrandt and the US Presbyterian minister, Timothy Keller, to explore more deeply how this parable is inviting us to more deeply to find a home in God, and in turn to allow God more deeply to find a home in us. Amen. |

Sermons and Blog

On this page you will find our online services, sermons and news. Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed